October 15

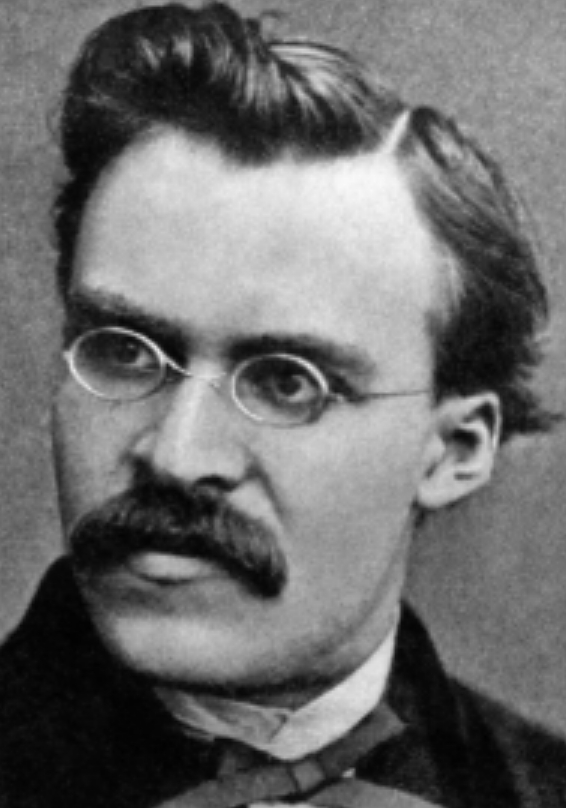

Friedrich Nietzsche

On this date in 1844, Friedrich Nietzsche was born in a town near Leipzig, Germany. “Fritz” was the son of a Lutheran minister who died when Friedrich was 4 and the grandson of two Lutheran pastors. At age 20, he wrote his sister that one could choose consolation in faith or pursue the truth no matter where it led. During a stint of mandatory military service, he suffered a serious chest injury. He then enrolled at the University of Leipzig, where he met and became friends with Wagner and Wagner’s wife.

A brilliant student, he was given his Ph.D. without an examination and joined the faculty of the University of Basel at age 24. Working as a hospital attendant during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, Nietzsche’s health was permanently weakened when he came down with diphtheria and dysentery.

His first book, The Birth of Tragedy (1872), was written when he was 28. It was followed by Human, All-Too-Human (1878-80), which ended his friendship with Wagner. Nietzsche resigned from his university position due to health problems. His outpouring of books includes Daybreak (1881), The Gay Science (1882), in which he wrote “God is dead,” Thus Spake Zarathrustra (1883-91), which he considered his most significant work, Beyond Good and Evil (1886), On the Genealogy of Morals (1887), which critiqued the priesthood, Twilight of the Idols (1888), The Case against Wagner (1888), in which he wrote that he “declares war” on the decadent composer who had turned back to religion, and The Antichrist (1888). “In Christianity neither morality nor religion come into contact with reality at any point,” he wrote in The Antichrist.

In 1889 he suffered a mental breakdown from which he never recovered and was nursed by his mother and sister for the remaining seven years of his life. In the last years of his life, he was reduced to a childlike state and was unable to converse with or recognize most people. Visitors would sometimes hear animal-like howls coming from his upstairs quarters. He did not live long enough to see his vast influence as one of the most respected thinkers of modern times.

Nietzsche is often falsely accused of fueling Nazism with his concept of the Ubermensch. He was not an anti-Semite, although he did not spare Judaism his trenchant criticisms any more than he spared Christianity. Nor was he a nationalist or militarist. (His sister, Frau Foerster-Nietzsche, who was an anti-Semite, forged 30 letters and put words into the mouth of her brother in compiling The Will to Power from manuscripts after his death.)

In Thus Spake Zarathustra, Nietzsche described his “higher man” as one who overcomes superstition: “I beseech you, my brothers, remain faithful to the earth, and do not believe those who speak to you of otherworldly hopes!” (D. 1900)

“After coming into contact with a religious man, I always feel I must wash my hands.” (Why I Am a Destiny, 1888)

“There is not sufficient love and goodness in the world to permit us to give some of it away to imaginary beings.” (Human, All-Too-Human, 1878)—

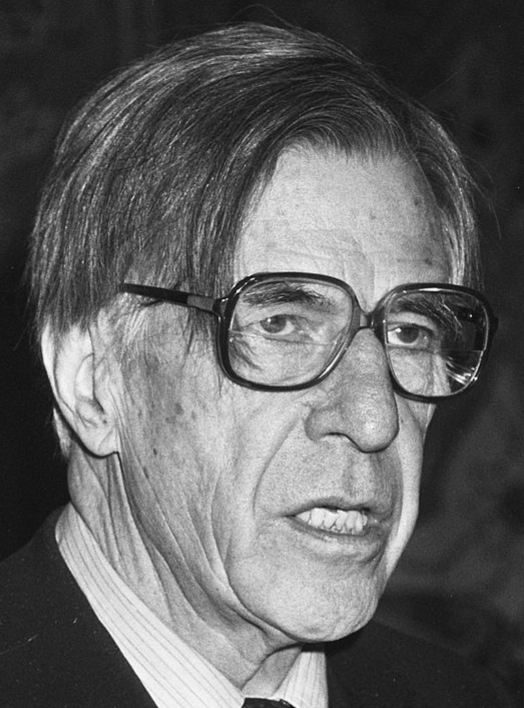

John Kenneth Galbraith

On this date in 1908, John Kenneth Galbraith was born in Iona Station, Ontario, Canada. He earned his B.S. at the University of Toronto in 1931 and his M.S. there in 1933. He received his doctorate at the University of California in 1934. Galbraith taught there and at Princeton before joining Harvard’s faculty. He was Paul M. Warburg Professor of Economics Emeritus at Harvard, where he retired in 1975.

His first best-seller was The Affluent Society, 1958, a warning about U.S. inattention to social welfare, which was followed by The New Industrial State (1967) and Economics and the Public Purpose (1973). His other books include many on economics, as well as Annals of an Abiding Liberal (1979) and A Life in Our Times (1981).

During World War II, Galbraith was in charge of wartime price control and was given the Medal of Freedom in 1946. A Democrat, he campaigned for Adlai Stevenson in 1952 and 1956, was ambassador to India for two years under John F. Kennedy and was an adviser and speechwriter to JFK, Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern. Galbraith was an early critic of the Vietnam War. He was married to Catherine Atwater and they had three sons. The American Humanist Association named Galbraith Humanist of the Year in 1985. D. 2006.

Dutch National Archives photo: Galbraith in 1982.

“I have managed most of my life to exclude religious speculation from my mode of thought. I’ve found that, on the whole, it adds very little to economics.”

—Galbraith, "What I've Learned," Esquire magazine (January 2002)

P.G. Wodehouse

On this date in 1881, humorist Pelman Grenville (“Plum”) P.G. Wodehouse was born. He lived with his parents in Hong Kong as a toddler, then was sent to be cared for by aunts in England. Wodehouse (pronounced “Woodhouse”) was educated at Dulwich College. His first novel was published when he was 21 in 1902.

The humorist, who wrote for Punch and other magazines, introduced the characters of the foppish, foolish Bertie Wooster and his invaluable valet Jeeves in The Man with Two Left Feet (1917). The series Wodehouse wrote about the pair became favorites with Bertrand Russell and other famous fans. In addition to his 120 books, Wodehouse occasionally moonlighted as a lyricist, writing the words for the song “Bill” in “Showboat,” for instance.

Living in occupied France in 1940, Wodehouse became subject to a Nazi decree that all English males under age 60 were to be immediately interned. He was sent to camps in Belgium and to Tost in Upper Silesia, where he remained until June 1941. He naively agreed to give light-hearted and innocuous interviews broadcast by the Germans, poking fun at his plight. The interviews were met with cries of treason in England, although he had many defenders. He moved to the U.S. and became a citizen in 1955 and was knighted in England in 1975.

Like many humorists, Wodehouse, known as “English literature’s performing flea,” was not religious. Biographer Robert McCrum wrote that Wodehouse was “agnostic towards matters of faith.” (D. 1975)

“In March 1972 [Wodehouse] was invited to attend Sunday service with President Nixon, but turned it down as ‘too much of a strain.’ He had no desire to leave Basket Neck Lane and, apart from his year in Tost, had never bothered much with religion, remaining strenuously agnostic.”

—Robert McCrum in "Wodehouse: A Life" (2004)

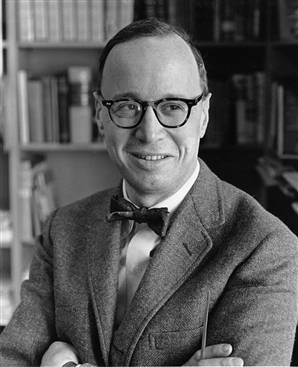

Arthur Schlesinger Jr.

On this date in 1917, Arthur Meier Schlesinger Jr., was born in Columbus, Ohio. He graduated from Harvard University summa cum laude in 1938 at age 20. He was a historian who was interested in liberal politics and the American presidency and who wrote more than 20 books, including The Age of Jackson (1945), The Vital Center: The Politics of Freedom (1949) and The Cycles of American History (1986). He became an associate professor at Harvard in 1946, but resigned to serve as a special assistant to John F. Kennedy until Kennedy’s death in 1963.

In 1965, he published a book about his time at the White House: A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House, which received the 1966 Pulitzer Prize and the 1965 National Book Award. He also won the 1946 Pulitzer Prize for The Age of Jackson (1946). He married Marian Cannon in 1940 and they had four children: Stephen, Katharine, Christina and Andrew. After their divorce in 1970, Schlesinger married Alexandra Emmet in 1971 and they had a son, Robert.

Schlesinger described himself as “agnostic” in Robert Kennedy and His Times (1978). In a blurb for Freethinkers: A History of American Secularism (2004) by Susan Jacoby, Schlesinger gave his support for freethought and the separation of state and church. He wrote, “In view of the tide of religiosity engulfing a once secular republic, it is refreshing to be reminded by Freethinkers that free thought and skepticism are robustly in the American tradition. After all, the Founding Fathers began by omitting God from the American Constitution.” D. 2007.

“As a historian, I confess to a certain amusement when I hear the Judeo-Christian tradition praised as the source of our concern for human rights. In fact, the great religious ages were notable for their indifference to human rights in the contemporary sense. They were notorious not only for acquiescence in poverty, inequality, exploitation and oppression but for enthusiastic justifications of slavery, persecution, abandonment of small children, torture, genocide.”

—Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., "The Opening of the American Mind," The New York Times, 1989

Roxane Gay

On this date in 1974, feminist writer and professor Roxane Gay was born in Omaha, Nebraska to Haitian immigrants. Her father was a civil engineer whose career meant that the family moved often. She has described spending much of her time reading and writing, and she fell in love with literature at an early age. She attended Yale for a year but left at 19, finishing her undergraduate degree in Nebraska, near her family. She earned a doctorate in rhetoric and technical communication from Michigan Technological University.

Gay founded the Illinois-based independent publisher Tiny Hardcore Press, is a contributing editor for Bluestem Magazine and a co-editor for PANK, a nonprofit literary arts collective. She has written for Salon, Jezebel, the American Prospect and the Rumpus. Her short stories have been featured in numerous collections, including Best American Short Stories 2012 and Best American Mystery Stories 2014.

In 2011 she published Ayiti, a short story collection. In 2014 she published the novel An Untamed State and The New York Times best-seller Bad Feminist, a collection of essays about feminism, race, gender and pop culture. Time magazine declared 2014 “the Year of Roxane Gay.” She is a nationally ranked Scrabble player and a professor of English at Purdue University. Though Gay describes her younger self as “a good girl who went to church,” she no longer believes in God.

SLOWKING photo: Gay in 2014. GNU Free Documentation License 1.2

“I try to understand faith and religion. I was raised by wonderful Catholic parents who were deeply faithful and taught us that God is a God of love. Even though I am lapsed, I respect that others turn to God and religion for guidance, for solace, for salvation. What I cannot respect is when that faith dictates how others should live their lives. I cannot respect when such faith tells some people that their lives are unworthy of dignity.”

—Gay, quoted in The Guardian, "Indiana is not protecting religious freedom but outright zealotry" (March 27, 2015)

Michael Lewis

On this date in 1960, author and financial journalist Michael Monroe Lewis was born in New Orleans to community activist Diana (Monroe) and corporate attorney J. Thomas Lewis. He attended Isidore Newman School, described in 2016 by The New York Times as elite. It was founded by a philanthropist as a school for Jewish orphans.

Lewis later described being on the receiving end of anti-Semitic taunts. Even though he was not Jewish, more than half his classmates were. Other alumni included NFL quarterbacks Eli and Peyton Manning, children’s author Mo Willems and Walter Isaacson, historian and Time magazine editor.

He earned a B.A. in art history from Princeton University and a master’s in economics from the London School of Economics in 1985, the year he married Diane deCordova in an Episcopal ceremony in the Princeton chapel. She had earned a master’s in comparative government from the London school. Lewis was working then as an investments associate at Salomon Brothers in New York, later transferring to London as a bond salesman.

The Salomon experience provided grist for the mill that became his first book. In addition to books, Lewis wrote prolifically for The Spectator, New York Times Magazine, Bloomberg, The New Republic, Slate and others. He joined Vanity Fair as a contributing editor in 2009.

His nonfiction books like “Liar’s Poker: Rising through the Wreckage on Wall Street” (1989), “The New New Thing: A Silicon Valley Story” (1999), “Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game” (2003), “The Blind Side: Evolution of a Game” (2006) and “The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine” (2010) built and cemented his reputation as a financial analyst/muckracker.

Several others followed, including “The Undoing Project: A Friendship that Changed Our Minds” (2017). It explored the Nobel Prize-winning collaboration of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky on how the human mind works. “The Premonition: A Pandemic Story” was published in 2021.

Critic Tom Bernard called him “the best satirist writing in English” and “the reincarnation in the United States of Evelyn Waugh.” (New York magazine, Sept. 30, 2011) “The Blind Side” (2009), “Moneyball” (2011) and “The Big Short” (2015) were adapted as major feature films.

“The Blind Side” details how Isidore Newman classmate Sean Tuohy and his family of evangelical Christians adopted Michael Oher, a troubled, illiterate and rebellious African-American, and transformed him into a National Football League star with a college degree.

“[Lewis] basically had a key to our house,” said Leigh Anne Tuohy. “Whenever he came to town, we made him go to church. We said, ‘If you want to talk to us, you’re coming to church.’ ” To their dismay, Lewis, an atheist, resisted conversion. “Lord knows we tried,” said Sean Tuohy. “We had people praying for him.” (Ibid.)

A gentile, Lewis could ladle on the sarcasm when he felt like it, as an article headlined “Toy Goy” showed. “Most years I commemorate the flight of the Jews through the Sinai to the Promised Land by witnessing a far more hectic flight of the Jews through the traffic jam to the airport, then looking around to see what they have neglected to finish. Each of these annual occasions revives my sympathies for the much maligned Pharaoh.” (The New Republic, April 26, 1993)

After his marriage to deCordova ended, he wed Kate Bohner, a journalist and financial executive, in 1994. A third marriage followed in 1997 to Tabitha Soren, a fine art photographer and entertainment journalist. They had two daughters, Dixie and Quinn, and a son, Walker. Tragically, Dixie died in 2021 at age 19 when a car driven by her boyfriend hit a semi tractor-trailer head-on near Truckee, Calif.

PHOTO: Lewis at a 2015 screening in Hollywood of “The Big Short” at the TCL Chinese Theater (formerly Grauman’s); Kathy Hutchins / Shutterstock photo.

CESAR [a Romanian priest]: But they are used to having visitors, so it shouldn’t be a problem. But what is your religion?

—Lewis, detailing his attempt to enter a monastery in Greece (Vanity Fair, Sept. 6, 2010)

LEWIS: I don’t have one.

CESAR: But you believe in God?

LEWIS: No.

CESAR: Then I’m pretty sure they can’t let you in.