June 19

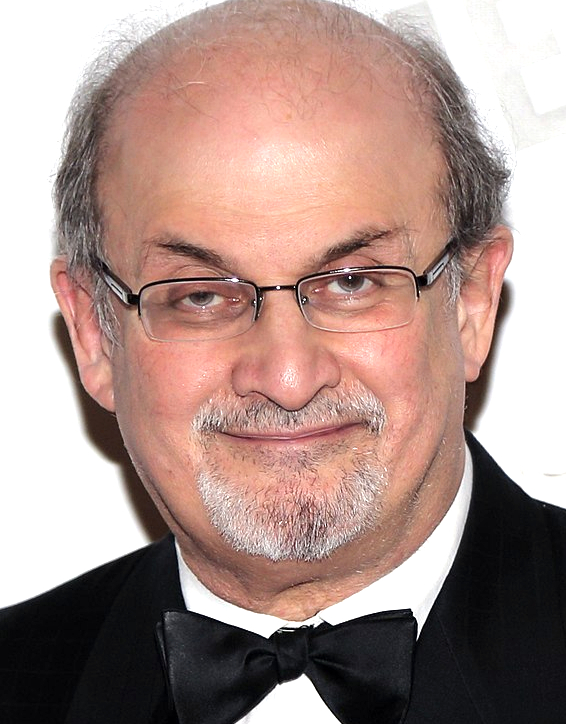

Salman Rushdie

On this date in 1947, Salman Rushdie was born in Mumbai, India, into a middle-class Muslim family. At 14, Salman was sent to Rugby School in England. In 1964 his family moved to Karachi, Pakistan. Rushdie graduated in 1968 from King’s College, Cambridge. After a fling at acting, television and freelance copy writing, he saw his first book published in 1975, a sci-fi adventure called Grimus. Midnight’s Children, 1981, won the Booker Prize and catapulted Rushdie at age 33 to international attention. Shame followed in 1983.

His novel Satanic Verses (1988), which was banned in India and South Africa, brought down the notorious death fatwa upon him by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini on Feb. 14, 1989. As V.S. Naipaul understatedly put it, the fatwah was “an extreme form of literary criticism.” Rushdie was forced to go into hiding. A $1 million bounty was placed on his head. The reward for his death was doubled in 1997. The Iranian government officially rescinded the fatwah in September 1998, although at least one ayatollah later issued his own.

Rushdie’s nonfiction essays from 1992 to 2002 appear in the book Step Across This Line. In one essay for The New York Times (Nov. 27, 2002), Rushdie wrote: “If the moderate voices of Islam cannot or will not insist on the modernization of their culture — and of their faith as well — then it may be these so-called ‘Rushdies’ who have to do it for them. For every such individual who is vilified and oppressed, two more, ten more, a thousand more will spring up. They will spring up because you can’t keep people’s minds, feelings and needs in jail forever, no matter how brutal your inquisitions.”

In a column headlined “Slaughter in the Name of God” (Washington Post, March 8, 2002), Rushdie wrote: “In India, as elsewhere in our darkening world, religion is the poison in the blood. Where religion intervenes, mere innocence is no excuse. Yet we go on skating around this issue, speaking of religion in the fashionable language of ‘respect.’ What is there to respect in any of this, or in any of the crimes now being committed almost daily around the world in religion’s dreaded name?”

He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2007 for his services to literature. Rushdie has married five times and has two sons, Zafar, born in 1979, and Milan, born in 1997. He became an American citizen in 2016. Rushdie spoke at FFRF’s national convention in San Francisco on Nov. 2, 2018, when he accepted the Emperor Has No Clothes Award. Quichotte, his 14th novel, was published in 2019 and was inspired by Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote.

Rushdie was attacked onstage in August 2022 at the Chautauqua Institution in Chautauqua, N.Y., as he was preparing to start a lecture. His alleged assailant, 24-year-old Hadi Matar of Fairview, N.J., whose parents were Lebanese immigrants, stabbed him about a dozen times, which resulted in Rushdie being put on a ventilator and hospitalized for six weeks. Though he recovered, he lost the sight in his right eye and the use of his left hand.

PHOTO: Rushdie in 2014 at the PEN American Center in New York; © Ed Lederman under CC 2.0

“I’m a hard-line atheist, I have to say.”

—Rushdie, interviewed on "Bill Moyers on Faith & Reason" (PBS, June 23, 2006)

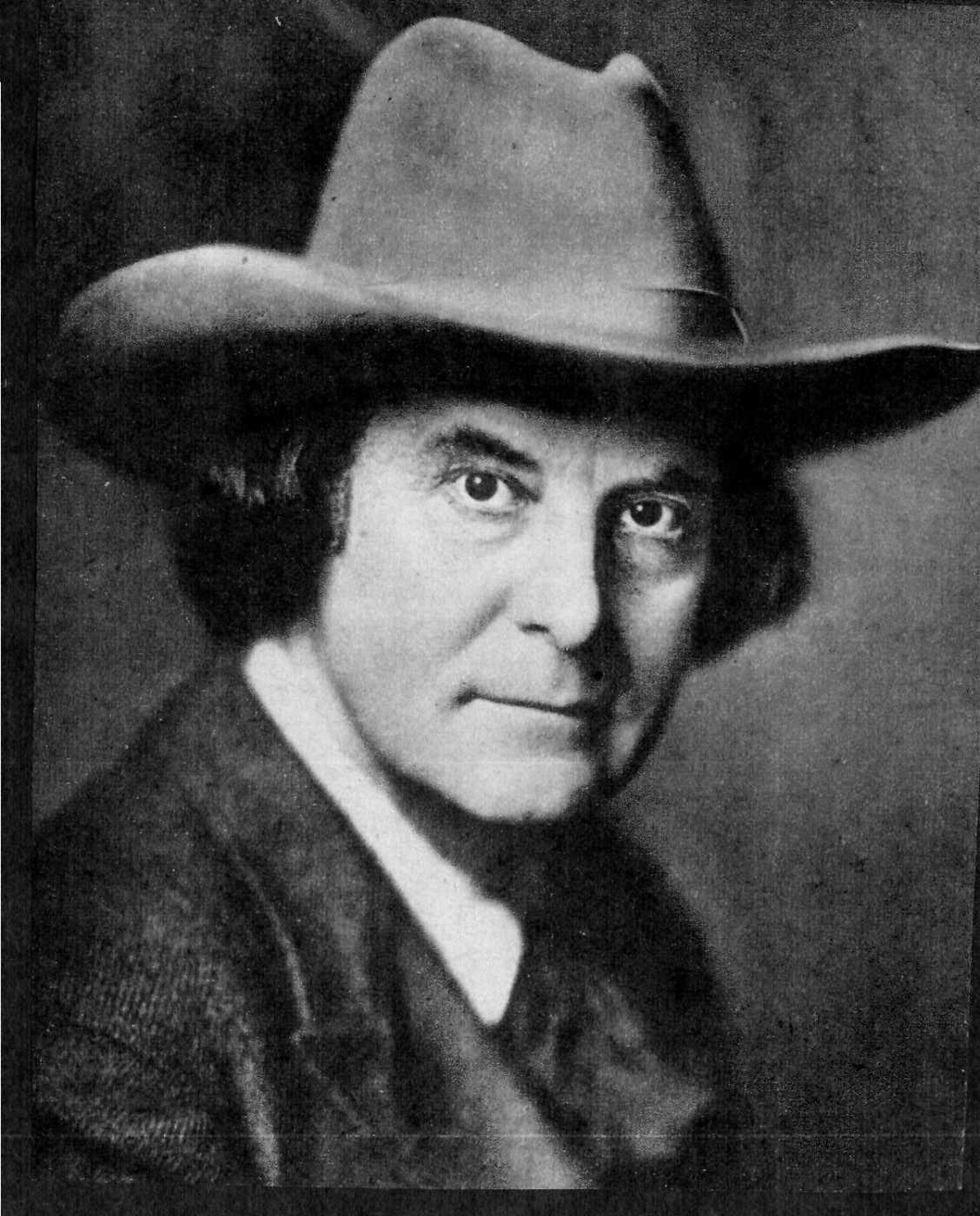

Elbert Hubbard

On this date in 1874, Elbert Hubbard was born in Bloomington, Illinois, the son of a country doctor. During his youth, the family moved to Buffalo, New York. Hubbard joined one of the first successful mail order businesses, JP Larkin of Buffalo, selling his interest in it at 36. After a trip abroad, he established Roycroft Printing Shop in East Aurora, New York, producing what are considered some of the finest handmade books of the 19th century, serving clients such as Henry Ford, Teddy Roosevelt and Queen Victoria.

Hubbard published several periodicals, including the monthly The Philistine (which printed his famous 1899 essay “A Message to Garcia”) and The Fra, also a monthly, with circulations that grew into the tens of thousands.

Hubbard, a firm freethinker, wrote eight books himself and produced a series, Little Journeys to the Homes of the Great (1895-1909), including one little book about Robert Green Ingersoll, the 19th century’s most well-known “infidel.” Gradually, Hubbard created a Roycroft community, including factory, blacksmith shop, farms, bank and an inn that is still standing. East Aurora today houses many of his artifacts in an Elbert Hubbard Museum. Hubbard became a popular lecturer and was hired as a columnist by Hearst Newspapers. He and his freethinking wife Alice Hubbard went down on the Lusitania to a watery grave on May 7, 1915. (D. 1915)

“When you once attribute effects to the will of a personal God, you have let in a lot of little gods and evils — then sprites, fairies, dryads, naiads, witches, ghosts and goblins, for your imagination is reeling, riotous, drunk, afloat on the flotsam of superstition. What you know then doesn’t count. You just believe, and the more you believe the more do you plume yourself that fear and faith are superior to science and seeing.”

—Elbert Hubbard section, "An American Bible," edited by Alice Hubbard (1912)

Juneteenth

Today is the anniversary of Juneteenth, the oldest nationally celebrated commemoration of the ending of slavery in the United States, dating to 1865. On that date, Union soldiers landed at Galveston, Texas, with news that the Civil War was over and the enslaved were now free, enforcing the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. Juneteenth became a federal holiday in 2021. All 50 states and the District of Columbia now recognize it through legislation or executive action as either a holiday or day of special observance.

—

Supreme Court Affirms No Religious Test for Public Office

On this date in 1961, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its unanimous decision in Torcaso v. Watkins, overturning a provision in the Maryland Constitution requiring that “a declaration of belief in the existence of God” be required as a qualification for any office of profit or trust in the state. Roy Torcaso, an atheist, had been asked to become a notary public at the Bethesda construction company where he worked and refused to swear to a religious oath of office in circuit court.

The Maryland Court of Appeals held, “The petitioner is not compelled to believe or disbelieve, under threat of punishment or other compulsion. True, unless he makes the declaration of belief he cannot hold public office in Maryland, but he is not compelled to hold office.”

The high court rejected such a rationale, saying it “cannot possibly be an excuse for barring him from office by state-imposed criteria forbidden by the Constitution.” Roy had asked the court to find the state constitutional requirement in violation of Article VI of the U.S. Constitution, which mandates that “no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.” In a footnote the court noted: “Because we are reversing the judgment on other grounds, we find it unnecessary to consider appellant’s contention that this provision applies to state as well as federal offices.”

Torcaso died in 2007 at age 96 at the Himalayan Elderly Care assisted living home in Silver Spring from complications of prostate cancer. “The point at issue,” he said in refusing to take the oath, “is not whether I believe in a Supreme Being, but whether the state has a right to inquire into my beliefs.”

“[I]t was largely to escape religious test oaths and declarations that a great many of the early colonists left Europe and came here hoping to worship in their own way. It soon developed, however, that many of those who had fled to escape religious test oaths turned out to be perfectly willing, when they had the power to do so, to force dissenters from their faith to take test oaths in conformity with the faith.”

“We repeat and again reaffirm that neither a State nor the Federal Government can constitutionally force a person ‘to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion.’ Neither can constitutionally pass laws or impose requirements which aid all religions as against nonbelievers, and neither can aid those religions based on a belief in the existence of God as against those religions founded on different beliefs.”

—Justice Hugo Black for the U.S. Supreme Court, Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488 (June 19, 1961)